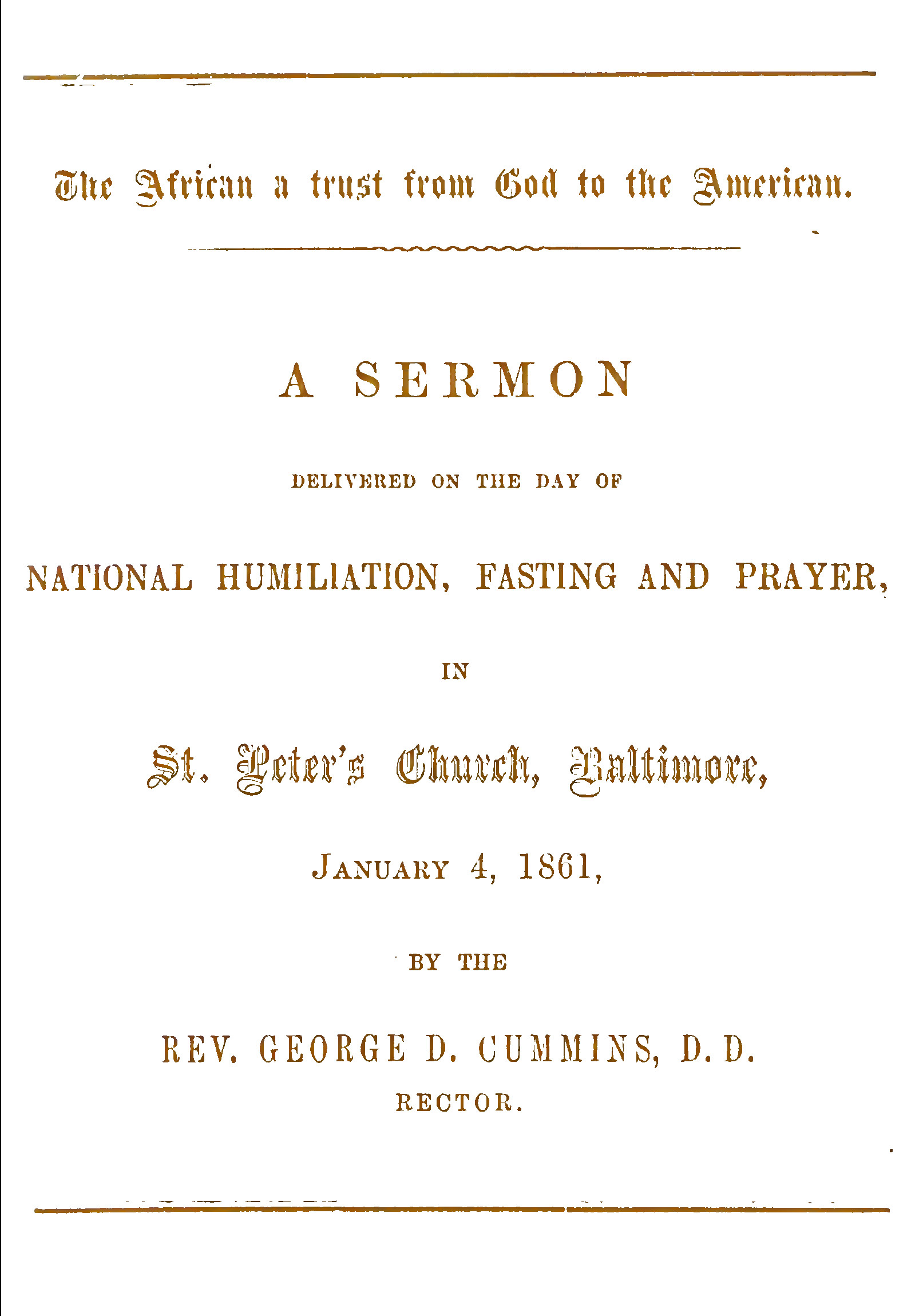

S

E R M O N

Jan. 4, 1861

Isaiah, LXV:8

|

Thus saith the Lord,

as the new wine is found in the cluster, and one saith, "Destroy it not;

for a blessing is in it," so will I do for my servants' sakes, that I

may not destroy them all.

|

We are

assembled today in the House of God under

circumstances most solemn and affecting to every Christian heart, and

at a period of our national history fraught with imminent peril. The

Chief Magistrate of a great nation has called its people to keep this

day holy by humiliation, fasting and prayer before God, that "His

omnipotent arm may save us from the awful effects of our own crimes and

follies."

If an inhabitant of some other planet, or some

distant region

of the globe, could be present among us to-day for the first time, he

might ask, with unfeigned surprise, whence arises the need of this

solemnity, and what is the fearful peril which casts its dark shadow

before it over the land, like an eclipse of the sun at noonday? Is

some foreign invader off the coasts of the land, with an overwhelming

force, threatening to burn your cities, desolate the country, and

subject it anew to the yoke of foreign tyranny? or is the noisome

pestilence abroad on the wings of the wind, making the whole land a

Baca, or vale of weeping over its ravages, and have ye met

to implore God to arrest the destroying angel? Nay, not these are the

perils from which we seek relief by prayer and penitence; but an evil

which we would gladly exchange for the pestilence from God or invasion

from a foreign foe. Willingly would we now accept David's choice, when

God gave to him liberty to elect one of three

fearful modes of Divine punishment, war, pestilence or famine, and say,

with the King of Israel, "Let us fall into the hand of the Lord,

and

not into the hands

of man."

No—we should have to reply to the visitor

from some

other sphere—we are not trembling before the rapid approach of a

foreign foe, or pestilence, or famine; but this is our peril. The

people of this once happy and heaven-blessed land, are no longer an

united people in heart and brotherly love and generous sympathy; but,

though of one blood, of one race, of one language, of one literature,

of one religion, of one inheritance in the past, and possessing one

hope for the future, are so inflamed by sectional hatred and jealousy

as to be almost ready to plunge into all the horrors of civil and

internecine war; and having found no hope of deliverance from men,

from statesmen and men of policy, we now turn to God and ask Him to

turn the hearts of men to peace and conciliation, and to save us from

anarchy and ruin.

As an ambassador of Him whose birth was

hailed by angels as bringing "peace on earth and good will towards men"

and whose sublime title is "Prince of Peace," it is my part to-day, not

only in solemn prayers aud litanies, but from the pulpit, "to labor for

peace;" and a single word which might increase strife would be sadly

out of place at such a time and in such a service. Nor do I design to

utter one such word. But there does seem to be a very special

appropriateness in occupying this hour, in taking a Christian view of

the great question which underlies the present crisis in our national

affairs, and of our conscientious obligations arising out of it.

It cannot be denied by any that the existence of one

element in our national life, is that out of which has arisen all our

troubles; that the presence in our midst, of the African race,

numbering now one-sixth of the population, and for the most part in a

state of involuntary servitude, is the causa causans, which prejudice

and passion have fed upon until we awaken to see a yawning gulf of

destruction before us, from which only an Omnipotent Arm can save us.

Were it not for the intermixture of the two races, the Anglo-American

and the African, the presence of two civilizations, we can scarcely

imagine any serious cause of danger arising to threaten the perpetuity

of this nation, unless it should spring from the vices ever following

in the train of luxury and inflated prosperity. But this country is

divided geographically between two sections, marked by two diverse and

yet not necessarily antagonistic social systems; fifteen of the

thirty-three States of the Confederacy being States where African

slavery is recognized and established by law.

Now, as to the. political aspect of the slavery

question, I do not propose to-day to utter a word. It is the glory of

the Protestant Episcopal Church in this

land that her ministers and her bishops, her Ecclesiastical Councils,

both State and National, have ever kept aloof from intermeddling with

this vexed question. Though existing in every State of the Confederacy,

from Maine to Texas,

and from the Atlantic

to the Pacitic, her ministers, with scarce an exception, have deemed it

a subject not lying within their province to settle; and her

representatives from every section have met in General Convention for

seventy-five years, from the first session in New York in 1785, under the

patriarchal Bishop White, to the last in Richmond

in 1859; and in all these

not a word on this subject of national politics has been heard to

interrupt the flow of harmony and brotherly love. From this true

position of a teacher of religion and a guide in spiritual matters

alone,

it is not my purpose to depart. And if the Union

of these States

must be shattered by the agitation of this question, the future

historian of these times, shall not point to the Protestant Episcopal

Church, as having a part of the guilt lying at her door.

I shall, therefore, not enter into a discussion

whether African slavery

be an advantage or a disadvantage to the well-being of a State—whether

certain conditions of climate and soil and culture render it

necessary or not—or whether the Constitution protects or prohibits it

in the national territories. Upon all these questions I have the

right

to form and hold an opinion, as a private citizen of the State and

Nation, but no right to bring them into this holy place and promulge

them to you.

But there is a moral and religious phase of the question of African

slavery, as it exists among us, which is strictly within my province to

discuss. And it is this aspect of the subject which has reached such a

complexion, that every conscientious Christian living where domestic

slavery exists, is called upon to answer in the light of his duty to

God for his position towards it, and his responsibilities arising out

of it.

For thirty years past a persistent,

unwearied

and cumulative effort has been made to train the mind of one great

section of our country, and that the largest and strongest, to regard

slavery and slaveholding under all circumstances as a moral wrong, a

wrong against God and man, a violation of His will and word, and a

crime against humanity; and of course a sin which excludes all who

have a part in it from the kingdom of grace here, and the kingdom of

heaven hereafter. By the press, secular and religious, by books and

tracts without number, by the writings of novelists, by the teachings

of schools and colleges, by denunciations from the pulpit and lecture

room, by agitations in ecclesiastical conferences, synods and

assemblies; by all these agencies multiplied a thousand fold and

repeated

through the life-time of a generation, the result has been reached; and

a majority of the citizens of one great section of the country, where

slaveholding does not exist, have been brought to the conviction that

their brethren of the other section are guilty in this thing of a crime

against their fellow men and a sin against their God. This deep

feeling

has extended into other lands, where, rather we might say, it

had its origin, and Protestant England and Scotland,

and Catholie France

and Ireland,

have united in our condemnation.

Turning our gaze to

that section of our land visited with such severe condemnation,—what

do we behold? A moral waste? A barren wilderness as to its religious

character? Communities given over to the powers of darkness, and not a

ray of holy light to illumine the blackness? Nay, the Church of Christ,

existing in all its

integrity and fulness of spiritual life; powerful and vigorous

Churches; ministers of Christ in every quarter, and numbered by

thousands; communicants at the altars of the Churches, numbered by

hundreds of thousands; holy men and women of faith and prayer, proving

the reality of religion in lives consecrated to self-sacrifice and

self-denying Christian toil; a type of piety unsurpassed for excellence

and simplicity and purity in any age or nation of the globe;

benevolent agencies in active exercise for diffusing the gospel

throughout the world and among the spiritually-destitute at home;

missionary societies sending forth evangelists to India and China and Burmah and Africa;

philanthropic societies ministering to the poor, the sick and the

prisoner; Howard associations, not less distinguished for heroic

daring amidst the pestilence than the famous Florentine Brothers of

Mercy; the Gospel preached as faithfully as ever proclaimed by St.

Paul,

by Christ's true and faithful servants;

souls daily converted and added to the Church; revivals of religion,

the fruit of the Holy Spirit making the Gospel, the power of God, unto

salvation; learned Divines devoting their lives to the study of the

sacred Scriptures; public teachers of morals in schools and colleges;

seminaries for training youth for the Gospel ministry—in a word,

God's people, acknowledging His word as their guide, claiming His

Holy Spirit as their teacher, owning Christ to be their model and great

Exemplar.

I can speak more especially for the Church

of which I am an humble minister; that in this section where domestic

slavery exists, there are well-nigh fifty thousand communicants,

served by nearly seven hundred clergymen and presided over by sixteen

bishops, many of whom would have adorned the Church of Christ

in any age. And if not for all these, yet surely I may not

presumptuously claim to speak to-day for the ten thousand communicants

of the Protestant Episcopal Church in this State of Maryland. True,

indeed, not all of these are themselves holders of slaves, but all are

included in a like condemnation, if it be a just one; since to live

surrounded by a great and flagrant moral wrong, and not to be a witness

against it and to labor for its removal, is to be a sharer in its

guilt.

What then, is the attitude of the

conscientious Christians of the South towards this great question? I

venture to express the opinion that the time has come to let all

Christendom know what that posture is—what answer they have to make

at the bar of God when charged with upholding a system of iniquity. I

would speak then, to-day, in behalf of the Christian whose lot has been

cast amidst a social system where slavery is one of its marked

features. I speak not only for the Christian slaveholder, for I am not

one of the number, but also for that large class who have been born and

reared under its influence.

Let

me state the case of

one of these: He is born into life in a Southern clime and in a

Southern home, and almost the first faces with which he becomes

familiar are the dark faces of another race than the one which gave him

birth. The first guardian and nurse of his infancy is an African;

the

earliest playmates of his childhood are the children of this race; he

grows to manhood surrounded by their faces now become familiar, and

learns to regard them as a part of the household of his parents.

Now he

comprehends their position, that they are in a state of servitude to

the superior race; that they are the descendants of heathens and

savages who were brought from their distant homes in Africa, perhaps an

hundred years ago. Soon he finds that he must take upon him the

personal responsibility of being the master of such, and while

receiving the benefit of their labor to provide for their well-being,

and the well-being of their children. Seeking honestly to comprehend

all the duties and responsibilities of his relation, he sets himself to

ascertain all the truth concerning it. And the very first step he

reaches is one too patent to be overlooked by any, and that is this:

I. That he is not responsible for the presence of this race around him, nor for its condition of servitude—nor was his father any more

responsible for it; both received it as an inheritance, whether for

good or evil: still an inheritance he cannot decline, a burden he cannot

shrink from. He tries to trace back this institution to its source,

but finds it coeval with the existence of the nation, and that at the

time of the formation of the Confederacy, slavery existed in all but

one of the thirteen States of the Union.

Thus he finds it to have been a bequest from the mother country, Great

Britain; and looking into its history there, he traces its existence

to the very earliest periods of Saxon history; and still extending and

widening his view, he perceives it pervading all the great historic

nations, Italy,

Greece,

the Eastern kingdoms, and the chosen people of God, even up to the

time of the patriarchs. Still, this antiquity of slavery would not of

itself satisfy his mind concerning his duty towards it, nor of itself

justify it, for error and wrong may be hoary with age, as well as truth

and right.

II. Another step then is needed,—to

ascertain God's will concerning it, and a Christian's duty towards

the race in bondage, in the light of the teachings of the Word of God.

The entire argument concerning the teaching of the Bible as to the

moral and religious phase of slavery is one which might fill a volume

far better than a page of a sermon; and we must be content only to

mention its leading points.

1. The first of these is

the attitude which our Blessed Lord maintained during His earthly

ministry towards slavery and slaveholders. When our Saviour appeared on

the earth, domestic servitude existed, by law, throughout the entire

Roman Empire, from Britain

to Parthia,

and no part of the immense dominion of the Caesars was exempt from it.

Slaves were acquired by war, by commerce, by inheritance, and even

free-born Romans could be reduced to slavery, under certain circumstances, by the operation of law. In the population of Italy,

under Augustus, there were three slaves to every free man. The Romans,

who were masters of Judea,

transported their

slaves thither, as an indispensable part of their domestic

arrangement. The Divine Redeemer, on His missions of mercy, could not

fail to be brought into contact with the system. And so, indeed it

proved, for one of His first and most striking miracles of mercy was

wrought upon a slave of a Roman centurion, and in answer to the

prayer of the master; and it was of this Roman slaveholder that Jesus

said, "I have not found so great faith, no, not in Israel."

The silence of Jesus with reference to the moral aspect of slavery is

that which is most significant to a Christian man in determining his

duty towards it. He did not shrink from the most severe denunciations

of the flagrant and crying sins of the men of his time for fear of personal injury

to himself. Let

any one who would be convinced of this read the 23d

chapter of St. Matthew's gospel, and hear the stern and overwhelming

rebukes which fell from the lips of Christ against the prevailing sins

of the people. Hypocrisy, envy, malice, uncleanness, extortion,

oppressing the poor, blood-guiltiness, all are charged home upon the

people, until the storm of his indignation falls in one thunderbolt

of—"Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the

damnation of hell?" [St. Matthew, xxiii, 13--33] Yet in all the list of

woes, there is none pronounced against slaveholding or the slaveholder.

2. The next point in the Scripture

argument is the attitude of the apostles of Christ towards the same

system. These inspired and holy men went forth at the command of their

master to preach the gospel and lay the foundations of His church. One

of them especially, St. Paul,

traveled through a great portion of the Roman

Empire, every

where coming into direct and close contact with slavery. Yet in all his

preaching and in all his epistles to the churches planted by him,

there is not to be found one testimony against the wrong of slavery;

not one precept that it is the duty of masters to emancipate their

slaves, not a word of the sinfulness of slavery. All other offences of

man against his fellow-man are condemned unsparingly; but this is

strangely omitted, if it be the deadly sin it is now proclaimed by

some.

But look at the conduct and teachings of St. Paul more in

detail. In the city of Athens,

where he preached to the philosophers on Mars Hill, and reasoned with

the Stoics and Epicureans in the marketplace, three-fourths of the

population were slaves: yet not a word falls from his lips concerning

this chief feature of Athenian society in all that memorable discourse. At Corinth,

which was for so long a time the chief slave mart of Greece, St. Paul

resided for eighteen months in the exercise of his ministry, and

founded a church embracing both converted masters and slaves. To this

church he writes a letter full of inspired counsels, and among them

is this: "Let every man abide in the same calling wherein he was called," that

is, "called" into Christ's kingdom. "Art thou called being a servant? —

(a slave) — care not for it, but if thou mayest be made free use it

rather"—that is, if thy freedom is offered thee, accept it and enjoy

it. "Brethren, let every man, wherein he is called, abide therein with

God." [I Cor., vii, 20--24] At Ephesus, also, where slaves were very numerous, St.

Paul dwelt two whole years "preaching the things

concerning the kingdom of God." Here, too, these bondmen were brought

into the liberty of the sons of God and enrolled in His church. And

writing to them afterward, the apostle says, "servants? (slaves) be

obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with

fear and trembling, in singleness of heart, as unto Christ; not with

eye-service as men-pleasers, but as the servants of Christ, doing the

will of God from the heart; with good-will doing service, as to the

Lord and not unto men; knowing that whatsoever good thing any man

doeth, the same shall he receive of the Lord whether he be bond or

free." [Eph. vi, 5--9] Here slaves are charged to perform their duties of obedience

and single-minded service "as unto Christ," as accountable unto God

for fidelity to their masters.

The same

heaven-taught man, writing to Timothy concerning his duties towards the

churches over which the Holy Ghost had made him overseer, thus defines

the duties of slaves: "Let as many servants as are under the yoke

count their own masters worthy of all honor that the name of God and His doctrine be

not blasphemed. And they that have believing masters, let them not

despise them because they are brethren ; but rather do them service

because they are faithful and beloved, partakers of the benefit." [I Tim., vi, 1--2] Then

follows an injunction to Timothy to withdraw himself from persons who

taught a contrary doctrine. Of a like import is his teaching to Titus,

the bishop of Crete: "Exhort

servants (slaves) to be obedient unto their own masters, and to please

them in all things; not answering again; not purloining, but shewing

all good fidelity, that they may adorn the doctrine of God our Saviour

in all things.'' [Titus, ii, 4--10] "Crete

was full of slaves from the earliest times to which history carries

us."

As to the case of Onesimus, I prefer to quote

the language of the late Prof. Edwards, of the Andover Theological Seminary, one of

the first Biblical scholars of this century and one of the holiest men

who have ever adorned the cause of Sacred literature. He says,

"Onesimus was the slave of Philemon, a Colossian, who had been made a

Christian through the ministry of Paul. He absconded from his master

for a reason which is not fully explained. In the course of his flight,

he met with the apostle at Rome,

by whom he was converted, and ultimately recommended to the favor of

his old master. St. Paul would, under any circumstances, have had no

choice, but to send Onesimus to his master; the detention of a

fugitive slave was considered the same ofience as theft, and would, no

doubt, incur liability to prosecution for damages.'' [Biblical Repository, Oct. 1835]

This, then, is the argument from the New

Testament concerning slavery as a moral wrong. Every allusion to it by

inspired apostles recognizes it as a part of the social system

established by law, and enjoins fidelity in the discharge of the duties

arising out of it, and no where, in a single instance, is it declared

to be of itself sinful. But there is an indirect sanction of the

system, perhaps still more marked. The inspired writers of the New

Testament do condemn the abuses of the relation between master and

slave, do denounce the evils which were found existing along with it in

their day. These abuses or evils were indeed enormous among the Greeks

and Romans. In both nations the life of the slave was absolutely in the

power of the master. At Athens

oftentimes cruel and barbarous punishments were inflicted upon them,

sometimes the torture of the wheel. The Romans punished gross offences

among them by crucifixion. In Sparta they

were liable to the horrible cryptia or ambuscade, when the Spartan

youth were encouraged by their governors to fall upon the Helots at

night, or in unfrequented places, and murder them, that these youths

might be better fitted for the stern and cruel scenes of war. It

is an

insult to Christianity, whose spirit is one of infinite mercy and love,

to ask the question whether it approved or even tolerated such

evils?

The soul of every Christian revolts against all cruelty, all

injustice, all oppression in every relation of life. Jesus did

condemn all the evils which existed along with slavery, when he said,

"Blessed are the merciful.'' "Whatsoever ye would that men should do

unto you, do ye even so to them," The golden rule, which bade the

slaveholder treat the bondman with the same justice and kindness with

which he would wish to be treated if their relations were reversed.

And the apostles of Jesus likewise did not hesitate to warn Christian

masters against these evils, and to guard them from these abuses. "And

ye masters!" says St. Paul

to the Ephesians, "forbear threatening, knowing that your master also

is in heaven; neither is there respect of persons with Him."

Ephesians, v., 9. To the Colossians he writes, "masters! give unto your

servants (slaves) that which is just and equal, knowing that ye also

have a master in heaven;" Col.

iv. 1. "That this injunction cannot mean the legal enfranchisement

of the slave is clear," says Prof Edwards, "for why, in that case, were

any directions given to the slaves, if the relation was not to

continue." [Biblical Repository, Oct. 1835] And the same apostle denounces "men-stealers," or those who

unlawfully seduced freemen to slavery as on a par with murderers. [I Timothy, i, 10]

The argument to be drawn from these facts is, that inasmuch as the

apostles of our Lord did condemn the abuses which were connected with

slavery, and did prescribe the duties of both masters and slaves; that

they did indirectly recognize the system as not forbidden by the word

or will of God, and not of itself involving moral wrong, and their

practice everywhere was in keeping with this view; for in every place

where the Church was planted, slaveholders were admitted into its fellowship without hesitation. Philemon, of

Colosse, was but one of the pious slave-holders who was a "brother

dearly beloved and fellow laborer," [Philemon, i, 1] to St.

Paul.

That the Gospel of

Christ did much to ameliorate the condition of the slave, and remove

the evils of slavery, we joyfully acknowledge. It proclaimed with

trumpet tongue, charity, forgiveness, kindness and love. It elevated

the worth of the soul of the slave. It banished and extirpated the

gladiatorial combats which were always among the slaves trained for

this purpose. It taught the master that the slave had a common share

with him in sin and in redemption; that he was the purchase of a

common Redeemer's blood; and that in Christ there was neither bond nor

free. But it never, directly or indirectly, by precept or practice,

taught that slaveholding was a sin against God and a crime against man.

Nor did slavery cease to exist and prevail in

the primitive church of the first three centuries—the days of its

very highest purity, and when refined by the fires of martyrdom.

Ignatius, the bishop of Antioch,

who was torn to pieces by the lions in the Coliseum at Rome,

writing to Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, who, for his confession of

Christ, was burned at the stake, says—"Overlook not the men and maid

servants, neither let them be puffed up; but rather let them be more

subject to the glory of God, that they may obtain from Him a better

freedom. Let them not desire

to be set free at the public cost that they be not slaves to their own

lusts." [Epistle of Ignatius, chap. 2] But the early Church pursued the same course towards the

institution as the apostles did. It did not denounce it, nor seek

violently to overturn it. It recognized it as established by law and

permitted by the Providence of God, but admitted freely masters and

slaves to all its privileges and blessings—while at the same time it

sought to mitigate the evils existing along with it. Slaves, holding

the true faith, were taken into the service of the Church, and ordained

to the ministry by the consent of their masters, without being

emancipated. Christian Emperors enacted laws to restrain the power of

inhuman masters. But the primitive Church rose, flourished and

triumphed over the Empire and left slavery to exist for centuries

afterwards.

By the light of this survey of

Scripture, and the history of the early Church, a Christian man whose

lot is cast amidst slavery in this age and nation, is enabled to

ascertain his duty towards it—and that is:

III,

To regard the African race in bondage (and in freedom too) as a solemn

trust committed to this people from God, and that He has given to us

the great mission of working out His purposes of mercy and love towards

them. The Anglo-American, the tutelar guardian of the African—this

is the lofty view to which we now rise. It is a study of intense

interest to trace the workings of God's Providence

in the mode He has chosen to effect His purposes concerning these

children of Ham. He has linked together, by a counsel of

infinite wisdom, the destiny of two races, more diverse from each other

than any two upon the globe. By the silver thread of His providence the

weakest race on the earth has been joined to the strongest, the oldest

to the newest, the most repulsive barbarism to the highest

civilization, the darkest superstition to the brightest and purest

Christianity. The feeble African parasite has found a prop on which

to climb on the noble oak of our Western land.

Other

races have at different periods of history been brought into close and

intimate relations with the African race, as the Roman and the

Castilian, but not to these has God entrusted this great work. To the

Anglo-Saxon and the American has He reserved the high honor. See

already how He is leading them on in the accomplishing of this work.

1. In abolishing the slave-trade, the fruitful source of every evil on

the Continent of Africa.

2. In stimulating

explorations throughout the land heretofore a terra incognita, thus

throwing open to Christianity and civilization a vast area peopled by

savage and degraded tribes.

3. Next, by the

missionary enterprise which has already translated the Bible into five

dialects and preached the Gospel to five millions of its people.

4. Above all, God has brought these people to our doors and placed them

in our homes, and said to us by His Providence, "take this child and

nurse it for me, and I will give thee wages." It is a sublime trust, a

stupendous work, worthy of the genius of this Christian nation, to

train, to discipline a race, to prepare them to work out the destiny

of a continent of one hundred and fifty millions of the same race. We

believe this to be the design of God, in the presence and condition of

the African in this land. And it is for us to decide whether we will

fulfil this high mission, or fail ignominiously under it. We cannot

decline the trust; it is ours by inheritance, and not by our seeking.

We cannot escape from its responsibilities, if we would. But how

shall we best fulfil that trust? This question involves and determines

our duty towards the Africans in servitude. How shall we prove

ourselves their truest friends—their best guardians? How discharge

our duty towards them in the light of our duty to the Master whom we

serve? Will it be by seeking hastily and violently to change their

condition, and bid them go forth from under our guardianship? As well

might we turn from our doors our children of tender years and send them

forth, helpless, into the world, exposed to every evil. It has been

well and truthfully said, that "it is not too much to say that if the

South should, at this moment, surrender every slave, the wisdom of the

entire world, united in solemn council, could not solve the question of

their disposal." But we may add, that the Providence of God will solve

it, in His own time, if we do not rashly thwart His plans, by our

short-sighted schemes. It may, indeed, be a long time before He

develops all His purposes towards the African race, and like ancient Israel,

He may prolong the time of their discipline. But in all His sublime

movements, there is ever the same slow and stately movement, ever the

absence of all haste. It required four thousand years to prepare the

world for the Advent of Christianity; and it may require four thousand

more to extend its triumphs over the whole earth. This is, indeed, a

feature of the Divine working most opposed to human schemes of

impatient haste. Many have lost all faith, in the final triumph of

truth and right, because of the slow progress made in a generation or a

century. Calvin's motto upon his signet-ring was the Psalmist's cry,

Quousque Domine? "How long, Lord?" But we can well be patient and

wait on Him, with whom a "thousand years are as one day."

But the chief

part of the question as to our duty towards the subject-race among us,

is not yet answered. What would God have us do for and towards them?

I reply:

1. To acknowledge him as of one blood with

ourselves, a sharer in a common humanity, a partaker of our hopes and

fears.

2. To labor for his salvation, for his

conversion from a savage and a heathen to a servant of Christ; to make

him one with us in the heritage of the Church of the Redeemer. Who can

suppose that if the Apostles of our Lord were now among us and in our

lot, that they would desire to do more? St. Paul did not at Corinth

and Colosse, nor did Timothy at Ephesus, nor did Titus at Crete.

This great work, the

Christians of the South are now zealously and earnestly striving to

perform. Throughout the fifteen slaveholding States of this Union,

there are men and women of God who feel the solemn duty resting upon

them to labor for the conversion of the slave. Every Christian

denomination of the South is engaged in this work, each seeking to

surpass the other in holy zeal. In some of the Churches, the Africans

professing the faith of Christ are numbered by tens and even hundreds

of thousands. Sunday Schools for their instruction in the doctrines

of the Gospel, abound in every part of the Southern country, and the

Gospel is preached to as many of the slaves, in proportion to their

numhers, as it is to any people of any section of this land. It was

lately proved by a most careful statistical scrutiny, that in the chief

commercial metropolis of this country, out of a population of 800,000

people, only 200,000 were provided with opportunities for having the

Gospel preached, while 600,000 could not find a place in any House of

God, if they so desired. Can this be said of the religious privileges

of the slaves of the South? Far, very far from it; the number of these

is exceedingly small who do not regularly hear the Gospel, or have it

within their power to hear it.

I

can speak with certainty of our own

branch of Christ's Church; and of that I can testify to-day, that in

all our large Southern Dioceses, the Church is successfully at work

in the conversion of the African. Says the Right Rev. Bishop

Green, of Mississippi, in

his last report to the General Convention of our Church: "Never before

have so many of the slave population been brought within the bosom of

the Church in this diocese. Never before has this field presented such an inviting aspect to the laborer in the spiritual

harvest. On every hand is observed the increasing desire on the part of

masters to give unto their servants the blessings of the Gospel and the

Church; and could we only comply with their pressing invitations to

preach the Word of Life to our 'Africa

at home,' the time would soon come when we should behold thousands of Ethiopia's

sons stretching

out their hands unto God." [Journal of Convention of 1859---Mississippi]

Says the truly

apostolic Bishop Davis, of South Carolina,

"about fifty chapels for the benefit of negroes on plantations, are

now in use for the worship of God and the religious instruction of

slaves. Many planters employ missionaries or catechists for this

purpose; many more would do so, if it were possible to procure them.

In one parish, there are thirteen chapels for negroes supplied with

regular services. The number of negroes attending the services of the

Church is very large and increasing annually." [Journal of Convention of 1859---South Carolina] Of Virginia, I can speak from a

residence of nearly eight years as a minister in two of her principal

cities. I believe facts would bear me out in the statement of my

belief, that in the State of Virginia,

the number of colored church members in all the denominations is equal

to, if not greater than that of the whites. All the Churches of that

commonwealth are alive to their duty toward the slave. All the pious

people of God feel most deeply their personal share in this obligation,

and seek the means

of discharging it.

The wealthy farmer builds for the slaves their own chapel, and

provides them a spiritual teacher. Not a Church edifice is

erected

in town or country, but provision is made within its walls for the

people of color. Flourishing Churches of colored people alone

exist in

every city and the larger towns. Sunday schools for adults and

children are under the care of all the Churches. In thousands of

homes, on every Sunday, masters and mistresses assemble a portion of

their servants for religious instruction. And this very

concern, for the religious welfare of the slave, tends to develop the

finest graces of the Christian character. Nothing so powerfully

nourishes the Christian graces of the parent, as the responsibilities

of his relation to the children whom God has given him. To a

Christian slaveholder, his slaves occupy to him a relation scarcely

less inferior to that of children; they form part of his household,

and for their temporal and eternal welfare he feels himself responsible

to God. How profound is this feeling of responsibility, I can

attest

from a personal residence among the pious masters of Virginia.

I "speak that which I know and testify that which 1 have seen." It

was my lot to minister at the altar of a Church where, along with

three hundred whites, fifty slaves knelt by them to receive the

sacrament of the Lord's supper. I have seen the master standing at the

chancel of the Church to act as sponsor in baptism for a faithful

slave who came forward to receive the sacred rite. I have seen

Christian women of the highest refinement and social position, sitting

down on every Lord's day in the midst of the classes of a Sunday

School of slaves, to instruct them in the knowledge of salvation. I

have known the slave girl in consumption to be taken into the chamber

of her mistress and nursed with a care equal to a mother's tenderness,

and the passage to the grave illumined by the light of Christian

sympathy and love. And I have seen a congregation of three thousand

slaves presided over by their regular pastor, the President of a

College, at the close of each sermon responding to the catechetical

instruction concerning the truths preached.

But it

will be said that according to the example of the apostles and the

early Christians, our whole duty towards slavery is not fulfilled until

we do our part to correct its abuses and remove the evils attendant

upon it—and we freely admit this. It is our part and duty following

in the steps of the apostles, to tell both masters and servants of

their mutual duties, and to warn them against abusing the relation in

which they stand to each other—to say to the servant "obey your masters in singleness of heart as unto the Lord !"—to say to the

masters, "give unto your servants that which is just and equal." And

we firmly and earnestly believe that there is not an evil connected

with slavery as it now exists in the Southern States, which in due time

would not be corrected and removed by the force of Christian sentiment,

enlightened by the Holy Spirit and guided by the Word of God. There is

power enough in the Christianity of the South to grapple with and

solve all the difficulties of this great question, if

left unhindered hy interference from without.

A word to the Christian

people of the State of Maryland

must be added to complete the survey of our duty in the position where

God's Providence

has placed us. There is much in your position towards the African race

which may comfort you amidst the perils of the present crisis. You have

not been wanting in the effort to discharge your trust, and to perform your duty towards this people. The slaves of Maryland

share equally with you all the inheritance of the Gospel and the Church of Christ.

Eighty thousand free people of color live within your borders, in

thousands of happy homes, unoppressed by any heavy burden, with

schools,

churches, and ministers of their own, with "none to molest them or make

them afraid." And last and not least, you have planted from among

these a Christian colony on the shores of Africa,

now part of a Republic, a brilliant gem on the dark forehead of that

continent, and the centre of light and knowledge and religion to

millions of its heathen and savage tribes.

Shall all

this work continue? Shall we go forward in the strength of God,

fulfilling the mission He has assigned to us toward the African, and

working out God's blessed purpose towards him through our agency? Shall

we bear him on with us to our and his final triumph? or shall we

perish with him? or leave him to perish? There is, to my mind, but

one thing that will determine these questions—the preservation OR

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE UNION OF THIS CONFEDERACY. May God in

His infinite mercy preserve it for us. for our children and our

children's children, for generations yet unborn. "Let thy work appear

unto thy servants, and thy glory unto their children. And let the

beauty of the Lord our God be upon us; and establish thou the work of

our hands upon us; yea, the work of our hands establish thou it."

|